Courtesy of wikipedia.org

At the end of each year, my stockbroker calls to talk about my portfolio and give me an assessment of the taxes I will owe. I appreciate his concern, but I’m also aware he’s giving me a mental health check-up: am I lucid enough to make financial decisions?

At 85, I sometimes feel obliged to defend my sanity, which isn’t easy given the competing notions of reality splitting the country. Scientific discoveries are disconcerting, as well. Many of them are about the human brain.

As an older person, I’m told I’m losing “fluid” intelligence–the capacity to handle abstract ideas with speed. On the other hand, studies show someone elderly has an improved capacity to eliminate irrelevant information and “increase[d] abilities in vocabulary, comprehension, reading other’s emotions, and knowledge.” (“Here’s Where Our minds Sharpen In Old Age,” Jim Davies, Nautilus, Issue 40, pg. 17)

In addition, people like me who were born in the 1930s have an advantage over those born in the 1960s. For some unexplained reason, we suffer less memory decline and have lower incidents of dementia. The good news for every U. S. adult over 65 is that dementia is on the decline, a drop of 2.5% since 2008.

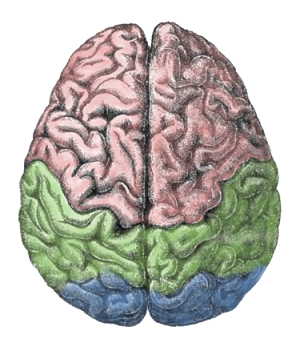

Unfortunately, the brain is slow to give up its secrets. Scientists know it folds in upon itself, forming wrinkles to accommodate its growth in a confined space, but they have no way to account for consciousness. What they do know is that consciousness is a “snapshot” in time, one the brain takes at the rate of 1/20th of a second. The universe moves faster, of course, which means consciousness misses “an awful lot of what’s happening around us.” (“Preludes,” by Tam Hunt, Nautilus, Issue 40, pg. 13.)

How we fill in the gaps helps shape our reality and affects how we relate to the outside world. Resignation syndrome is an example. In Sweden, several immigrant Syrian children fell into a trance once they learned they and their families were being deported. Some revived within a few months but one has been asleep for three years. The affliction is genuine though physicians are stumped as to the cause. It seems as if the children have rejected a world that has rejected them. (“Why These Children Fell into Endless Sleep,” by Suzanne O’Sullivan, Nautilus, Issue 40, pgs. 46-53.)

Given how little we know about our minds and the partial information it provides, it’s a wonder we leave our beds each morning. And yet we do. Is it because we are fools, as Puck surmises in Midsummer Night’s Dream. (III, ii, 115.) I’m inclined to think ignorance is part of our courage. Yet, I also know one truth is self-evident. Kings die as do paupers.

Homo sapiens are pawns in Nature’s progress. We make little of our own. Nonetheless, there’s no reason to despair. This last bit of information is the brain’s gift to us. Beyond biological destiny, we are free to add embellishments. Why else do science and art exist? And, if we grow old enough to become honest with ourselves, we might discover our greatest achievement is the comfort we give to one another.