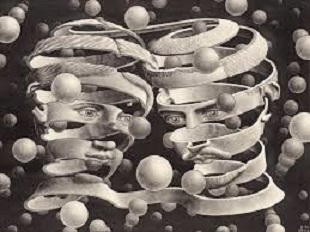

Bond of Union by M. C. Escher https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.54267.html

A question lingers in my mind three years after my mother’s death. Was I a dutiful daughter in her declining years? An earlier blog recounts an incident when I failed her. She’d taken a spill as the pair of us left a restaurant during a rain storm. She was 101 at the time and already suffering from memory loss. Given her condition, the mishap roiled in my mind for several days.

Finally, I decided I’d been guilty of placing my parent in a life-threatening circumstance and decided never to take her out again. Instead, I carried her favorite meals to her. Deprived of stimulation beyond her four walls, however, her acuity seemed to decline. By the time she died at 104, I decided I had been over protective.

Age is a much-feared disease and all who suffer it will die. Ponce de Leon dreaded the thought of growing old. A 16th-century Spanish Explorer, he secured his place in history as the traveler who searched for the fountain of youth. Like Herodotus who lived in 400 B. C. Greece, he hoped the myth that such a fountain existed was true. Sadly, he never found it or managed to recapture a single lost second of his life. Time’s direction is forward, and we grow old because of it.

At 87, my decline is undeniable. I need hearing aids and glasses. Last week a company installed a caption phone to improve my ability to understand what callers have to say. Mercifully, the installer left me with a manual—a rarity these days. Otherwise, I’d have been forced to search the internet for instructions, a procedure that seldom works for me.

Despite the diminuendo of my life, I have no plans to go gently into that good night; but I won’t take extreme measures either. Starving myself to extend my days strikes me as a living death. Nor will I arrange for my body to be frozen after I’m gone in the hope I can be resurrected in the future. (“The One Body Problem,” by Rachel Dodes, Vanity Fair, Feb. 2024, pg.98.) I’ve no doubt I’d awake with my wrinkles preserved but suffering from frostbite.

My goal as I age is to be at peace with my decline. That includes accepting the onset of dementia should it come. I see no handicap in living in the moment after recollection fades. One happy fact about the disease is that memory loss doesn’t affect creativity. A retired accountant who can no longer balance his checkbook, for example, has become a gifted photographer. (“Love, Dementia and Robots,” by Kat McGowan, Wired, March/April 2024, 70.) His story gives me hope that no matter the state of my memory, imagination will allow me to continue to spin yarns for many years.

Whether we like it or not, old age forces us to reframe who we are. We may no longer be doctors, lawyers, or candlestick makers, but we do keep our inner lives. Even René Descartes, the father of science and reason, wouldn’t deny that truth. I think, therefore I exist… even in my fantasies.

If dementia takes us to another place, that’s no proof we are lost. Erased memories may prevent me from reliving experiences with my friends, but who’s to say, they can’t enter mine? Technology and AI are beginning to ask that question.

Sometimes, a memory device can be simple. One is a musical pillow. Touch it and it plays songs from World War II. “We’ll Meet Again,” never fails to wake one elderly woman from her dreams. Hearing the music, she breaks into song. Her daughter, seated beside her, touches her hand, and then their voices rise together. The “reunion” may bring tears to the daughter’s eyes, but I suspect they are good tears. (Ibid, pg. 73)

I wish I had thought to enter my mother’s world instead of insisting she remain in mine. She didn’t seem unhappy where she was. I’d no need to drag her through the rain to keep her with me. I could have sought other ways to send my words through time and space to greet* her. If I had, it might have made all the difference.

*James Elroy Flecker, To a Poet a Thousand Years Hence